Boston's Summer Youth Employment Program

Designing for Efficiency and EquityAlicia Sasser Modestino, Northeastern University

Rashad Cope, City of Boston

Policy Brief 2023-1

September, 2023

Summary

Along with many cities across the United States, the City of Boston supports a vibrant summer youth employment program that connects low-income youth living in marginalized communities to positions where they learn valuable skills that set them up for future success. Rigorous research evidence has shown that summer jobs programs, like the Boston Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP), are a cost-effective way of improving a wide range of youth outcomes related to employment, education, and criminal justice involvement. Compared to other cities, the Boston SYEP operates as a coordinated ecosystem of workforce intermediaries that proved highly resilient during COVID, leading to an additional $4.1 million investment during summer 2020 to support four new tracks of programming, including a new Learn and Earn program.

Since then, the City of Boston and the other SYEP intermediaries have recognized the importance of increasing coordination and alignment across the ecosystem to “build back better” post-COVID. To lead this effort, the City has deepened its partnership with Northeastern University under a new multi-year project funded by the William T. Grant Foundation to address both the efficiency and equity challenges that the program has faced. Over the past two years, the research team has analyzed youth application and hiring records; interviewed youth, parents, employer-partners, and staff; and evaluated several pilot interventions, including a job matching algorithm, to increase both the number of jobs filled and the diversity of youth served.

This policy brief provides a summary of our research findings as well as an update on the City’s progress towards implementing a set of foundational recommendations. These efforts include expanding the number and type of summer opportunities, increasing access by streamlining application and hiring processes, and improving coordination across SYEP intermediaries to provide a range of high quality, skill building opportunities. As a result, the City made an unprecedented $18.7M investment in summer jobs in summer 2023, successfully employing over 9,000 young people ages 14 to 24, rebuilding the backbone for a more holistic and inclusive workforce development system for Boston’s youth.

Boston’s Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP)

Since the early 1980s, the Boston SYEP has relied on nearly $10 million in city, state, private sector, and philanthropic funding each summer to connect upwards of 7,000-10,000 youth with anywhere from 500-900 local employers. This significant investment in the City’s future workforce each year reflects two primary goals:

- To increase youth labor market attachment by providing youth with the tools and experience needed to navigate today’s job market on their own, and;

- To reduce inequality of opportunity across different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups by increasing access to early employment experiences.

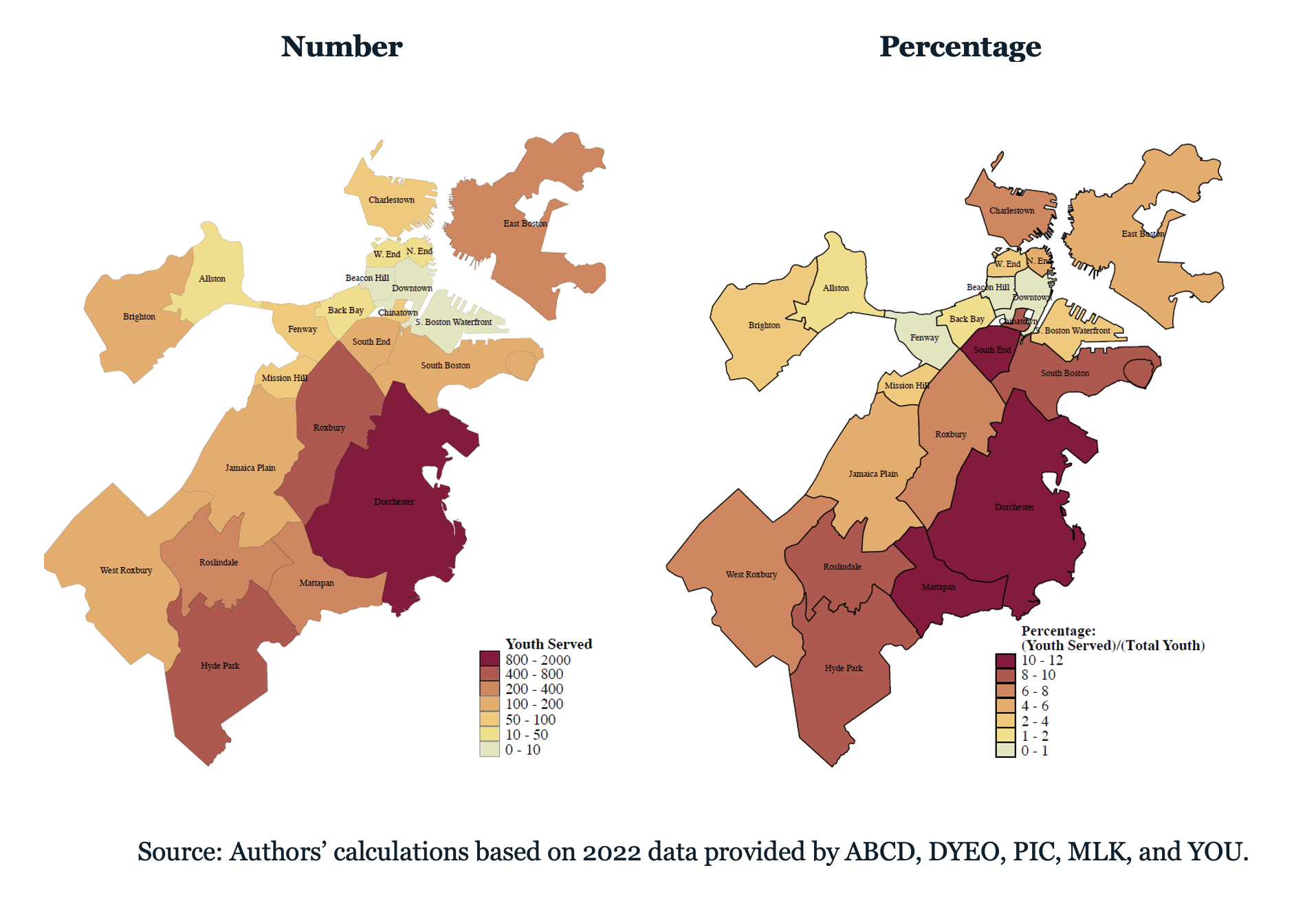

The program serves youth from all 23 of the City’s neighborhoods with greater representation among low-income communities of color such as Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan (see Figure 1). Survey data reveal that more than half of SYEP participants use their earnings to pay some type of household bill, such as groceries, housing, utilities or transportation—making the program an important source of support for low-income households during the summer.

Figure 1. The Boston SYEP serves youth from all 23 of Boston’s neighborhoods with greater representation among communities of color.

How do Youth Navigate the Boston Summer Jobs Ecosystem?

Compared to other cities, the Boston SYEP operates as a coordinated ecosystem that serves upwards of 10,000 youth each summer, braiding together multiple sources of city, state, and philanthropic support (see Table 1). All Boston city residents aged 14 to 24 years are eligible for the program and can apply to jobs through one of five intermediary organizations that typically specialize in serving different youth populations based on age, school type, and other risk factors. The exception is the City’s SuccessLink program operated by the Office of Youth Employment and Opportunity (OYEO) which provides open access to all youth and is the largest provider of summer jobs within the Boston ecosystem.

Each intermediary is responsible for reviewing applications, matching applicants with jobs, supervising placements, and delivering the program’s career-readiness curriculum. Youth may be placed in either a subsidized position (e.g., with a local nonprofit, community-based organization, or city agency) or a job with a private-sector employer where the employer pays the youth directly. Participants work a maximum of 25 hours per week for up to 7 weeks during July and August. Youth aged 14-18 are paid the Massachusetts minimum wage while youth leaders aged 19-24 earn slightly more. The career-readiness curriculum includes at least 20 hours of workshop training that cover exploring their skills and interests; learning about the job search process; and developing soft skills such as communication, collaboration, and conflict resolution.

Table 1. The Boston SYEP ecosystem braids together multiple funding sources across five primary intermediary organizations that target different youth populations.

| SYEP Intermediary | Number of Participants (pre-COVID) | Funding Sources for Support | Youth Population Served | Types of Jobs Offered |

| Action for Boston Community Development (ABCD) | 800-1200 | City of Boston, state, private philanthropy, other grants | Low-income youth typically age 14-15 years | Subsidized jobs primarily in daycares and day camps as well as community-based organizations |

| Boston Private Industry Council (PIC) | 2000-3000 | City of Boston, state, private sector employers | Youth age 16-19 years who are Boston Public School students | Subsidized jobs in daycares and day camps, non-profits, and healthcare. Private sector jobs in biopharma, hospitals, finance, banking insurance. |

| Office of Youth Employment and Opportunity (OYEO) | 3000-5000 | City of Boston | Youth age 15-18 years, older youth aged 19-24 years serve as peer leaders | Subsidized jobs in daycares and day camps, non-profits, healthcare, and city government |

| John Hancock MLK Scholars Program (MLK) | 500-600 | John Hancock | Youth age 15-18 years | Subsidized jobs in daycares and day camps, non-profits, healthcare, and business |

| Youth Options Unlimited (YOU) | 100-150 | City of Boston, other grants | Court-involved youth age 14-24 years | Subsidized jobs in community-based organizations |

Source: Authors’ categorization based on data and interviews from each intermediary organization.

During the summer of 2020, the Boston SYEP ecosystem proved highly resilient and pivoted to a hybrid format during COVID. While other cities such as New York, either scaled back or shut their summer job programs down, leaving thousands of young people unemployed, Boston invested an additional $4.1 million of CARES Act funding to employ the same number of youth, at the same number of hours, and the same rate of pay. The expansion during 2020 was made possible by the intermediaries working together to develop new opportunities to enable youth to safely engage in meaningful activities which continue today. These include a Learn and Earn program through which students earn money while taking college-level courses as well as a Virtual Internship program which supports businesses and community-based organizations with a platform of ready-made projects and dashboards to virtually manage collaborations with teams of youth workers.

What are the Benefits of Summer Youth Employment?

The Boston SYEP expansion during 2020 was based on our prior research which had shown the program’s large positive impacts on a range of economic, academic, and criminal justice outcomes for youth. We were able to measure these impacts based on a lottery system that was used prior to COVID where youth were assigned to jobs at random since the number of applicants exceeded the number of jobs every year. Using the lottery assignments, we compared the outcomes of SYEP participants selected at random to a set of similar applicants who did not win spots in the program (e.g., the control group). This allowed us to identify the impacts of the program separately from other factors that affect youth development over time.

Economic Outcomes: Even when the job market is relatively good, the Boston SYEP raises employment rates among youth and provides them with more meaningful work experiences than their peers. State administrative records reveal that only one-quarter to one-third of youth not selected by the program’s lottery system were able to find a job on their own. In addition, SYEP participants were more likely than their counterparts in the control group to report that they would consider a career in the type of work they did, had an adult they considered a mentor and could use as a reference in the future, and felt better prepared to enter a new job. These improvements in job readiness skills were linked to a 9-percentage point increase in employment and a 30 percent increase in wages during the year following program participation for opportunity youth of color aged 19 to 24 years.

Academic Outcomes: The Boston SYEP also increases high school graduation and boosts college enrollment by raising academic aspirations and improving work habits. Survey data showed that by the end of the summer SYEP participants are more likely to report that they plan to attend a four-year college or university compared to the control group. Work habits also improve markedly with a significant increase in the share of participants reporting that they know how to be on time and organize their work. These improvements in academic aspirations and work habits were linked to better attendance and grades, reducing drop-out by 22 percent and increasing on-time high school graduation. Private sector jobs were further shown to increase the likelihood of taking the SAT and enrolling in a four-year versus two-year college.

Criminal Justice Outcomes: The program also reduces criminal justice involvement by fostering community engagement and soft skills. SYEP participants show significant improvements in feeling connected with their neighbors and co-workers and knowing how to manage their emotions, ask adults for help, and resolve conflicts with a peer. These behavioral improvements were linked to a 30 percent reduction in both violent and property crime among SYEP participants relative to the control group during the 18 months after the program ended.

Overall Impact on Reducing Inequality: Across all of these domains—job readiness, academic aspirations, and soft skills—improvements were larger among African-American and Hispanic youth, suggesting that the Boston SYEP has the potential to reduce inequality across groups. A simple back-of-the–envelope calculation based on the increase in high school graduation and the reduction in criminal justice involvement suggests that the long-term benefits of the Boston SYEP outweigh the costs by more than 3-to-1. The lived experiences of youth, parents, and employers provide powerful testimonials and important insights confirming the program’s positive impact on youth, families, and communities (See Box 1).

Efficiency and Equity Audit: Summer 2022 Findings

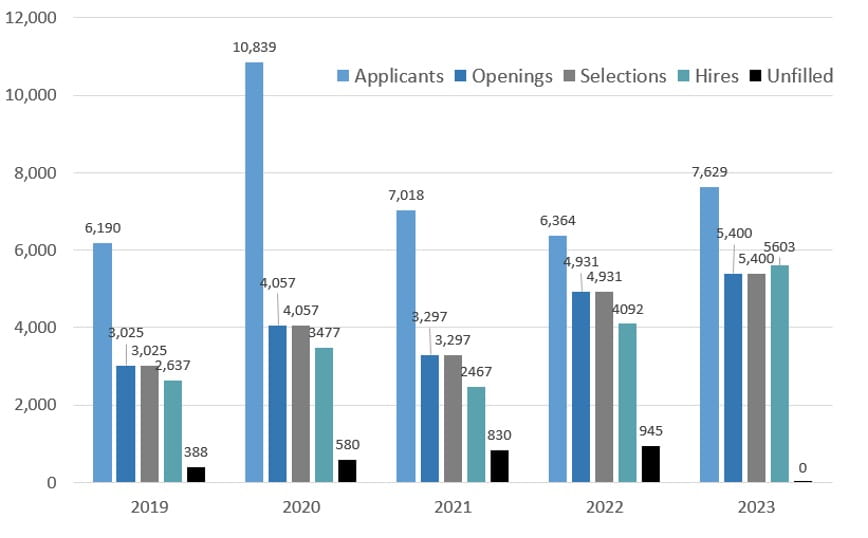

While the Boston SYEP’s decentralized ecosystem provided flexibility and opportunity during COVID, it also presented logistical challenges that have reduced efficiency and exacerbated inequities since the pandemic. We measure efficiency based on how many of the program’s job slots are filled each summer—or whether there are unfilled openings that leave youth unemployed, staffing shortages at nonprofits, and unspent funding. We measure equity based on how well youth selected for an opening are representative of the applicant pool—or whether there are disparities by race, ethnicity, and school type (e.g., exam or open enrollment).

What are the Challenges facing Boston’s Summer Jobs Ecosystem?

While the Boston summer jobs ecosystem was able to expand the types of opportunities available during summer 2020 and serve a more diverse youth population, these changes made matching youth to jobs more complex. This is because intermediaries needed to balance both the diverse career interests of youth as well as employer needs for each of the many types of positions, making random assignment no longer feasible.

However, the hiring platforms used by the intermediaries were not designed to process high volumes of applications over multiple employer-partners, cross-check matches for duplicate placements in real-time, and provide a user-friendly experience for youth to complete paperwork in a timely manner. As a result, the post-COVID selection and hiring process across the Boston summer jobs ecosystem has become inefficient, serving to slow down or even derail the hiring process for some youth. Moreover, the employer selection process, left unchecked, replicates many of the inequities that we see in the real-world labor market.

Given that one of the intended goals of the Boston SYEP is to level the playing field for low-income and BIPOC youth, City leaders sought to increase both the efficiency and equity of how jobs assignments are made. During the summer of 2022, Northeastern partnered with OYEO to perform an efficiency and equity audit of the SuccessLink application and hiring system. Below we summarize the key findings from our in-depth report based on interviews with youth, parents, employers, and SuccessLink staff as well as an analysis of the application, employer selection, and onboarding data from the SuccessLink (iCIMS) hiring platform.

Roughly one-third of youth fail to complete the application process, suggesting that there are significant barriers to participating. During the 2022 summer job cycle, we observed 6,364 unique youth profiles. Of those youth, approximately 33 percent (2,110) never fully completed a valid job application, suggesting that there are significant barriers to completing the application process. In a few cases, youth did not answer one or more of the screening questions correctly (e.g., birthdate) and OYEO staff reached out to correct these errors. However, 95 percent of invalid users were missing their social security number, indicating that supplying this information up-front is a potential barrier for youth applicants.

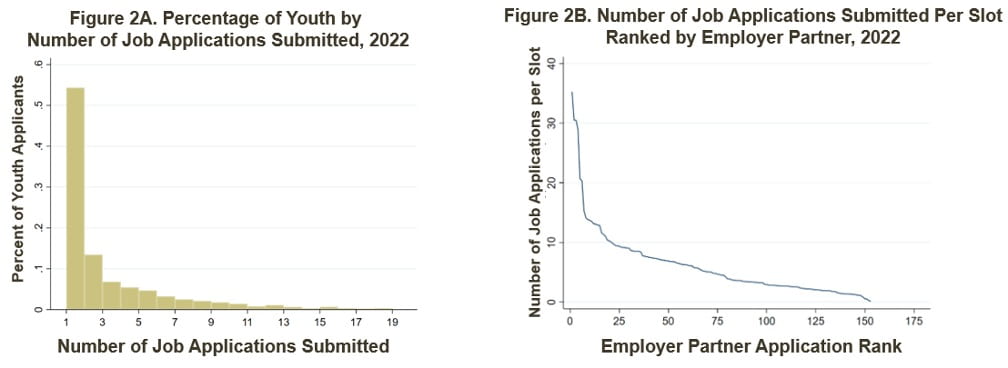

More than half (53 percent) of all youth apply to only one job, indicating that the application process is cumbersome. Although youth are encouraged to apply for up to 15 jobs, Figure 2A shows that 53 percent apply to only one job and upwards of 70 percent apply to three jobs or less. In part this is because the SuccessLink (iCIMS) hiring platform does not allow youth to search for positions easily nor to complete multiple applications seamlessly.

Some employers receive hundreds of applications for only a few positions while other employers receive only a handful, signaling a lack of information. Despite all of the job opportunities listed through the SuccessLink hiring platform, Figure 2B shows that some employers receive anywhere from 15 to 40 applications per open slot (oversubscribed) while others have fewer than one application per slot (undersubscribed). In part this is because some employers (e.g., Zoo New England) are familiar to youth or are located close to their neighborhoods (e.g., Dorchester YMCA) while others are less well-known or further away.

Figure 2. More than half of SuccessLink youth apply to only one job and many apply to the same job creating a severe mismatch between supply and demand.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data provided by the Office of Youth Employment and Opportunity

The combination of youth submitting too few applications and many applying to the same employers creates a severe mismatch that can leave youth unemployed and jobs unfilled. If most youth apply to only one job, then the chances of landing one of the oversubscribed jobs is slim to none. For example, the Dorchester YMCA received 355 applicants for just 33 positions, leaving 322 youth not hired—many of whom did not apply to any other position. Similarly, if many youth apply to the same job then the chances of filling a job are very low for other employers. For example, the BCYF Perkins Center received only 3 applicants for 20 positions, leaving 17 jobs unfilled at the start of the program.

Employers tend to select the same youth for multiple positions while other youth are not selected for any positions and these selections often show disparities by race and ethnicity. Only half of youth who applied through SuccessLink were selected by an employer and there were a substantial number of youth who received multiple offers, creating the need for OYEO to cross-check and back-fill positions. In addition, employers were nearly twice as likely to select white youth relative to the percentage of whites in the applicant pool. They also selected a larger proportion of native English speakers and students from Boston’s prestigious “exam” schools. These disparities persisted even when controlling for a variety of factors that could affect selections including age, neighborhood, previous participation in the program, the number and timing of applications submitted, and having uploaded a resume.

The hiring paperwork poses significant barriers such that up to 15% of youth who are matched to a job do not complete the onboarding process. Completing the hiring process involves up to 10 different steps—most importantly locating and uploading important documents (e.g., social security card, proof of residency, and a work permit). Youth took 25 days on average to complete onboarding with most taking upwards of 5-6 weeks, potentially delaying their start date. Hundreds of youth were unable to complete onboarding and could not be hired. Black and Hispanic youth were less likely to complete the hiring process, suggesting that documentation requirements may present a greater barrier to youth of color.

Improving Efficiency and Equity: Summer 2023 Progress

Interviews with each intermediary organization confirmed that these same efficiency and equity challenges exist across the Boston SYEP ecosystem. Working with the City, we piloted several interventions during 2022, including a job matching algorithm, to increase both the number of jobs filled and the diversity of youth served. We also co-created a set of actions to streamline the City’s application, selection, and hiring processes as well as improve job quality and increase coordination and alignment across the ecosystem. Many of these recommendations were implemented by the City through an unprecedented $18.7M investment in summer jobs, resulting in an upwards of 9,000 young people ages 14 to 24 engaged in a variety of paid opportunities during the summer of 2023.

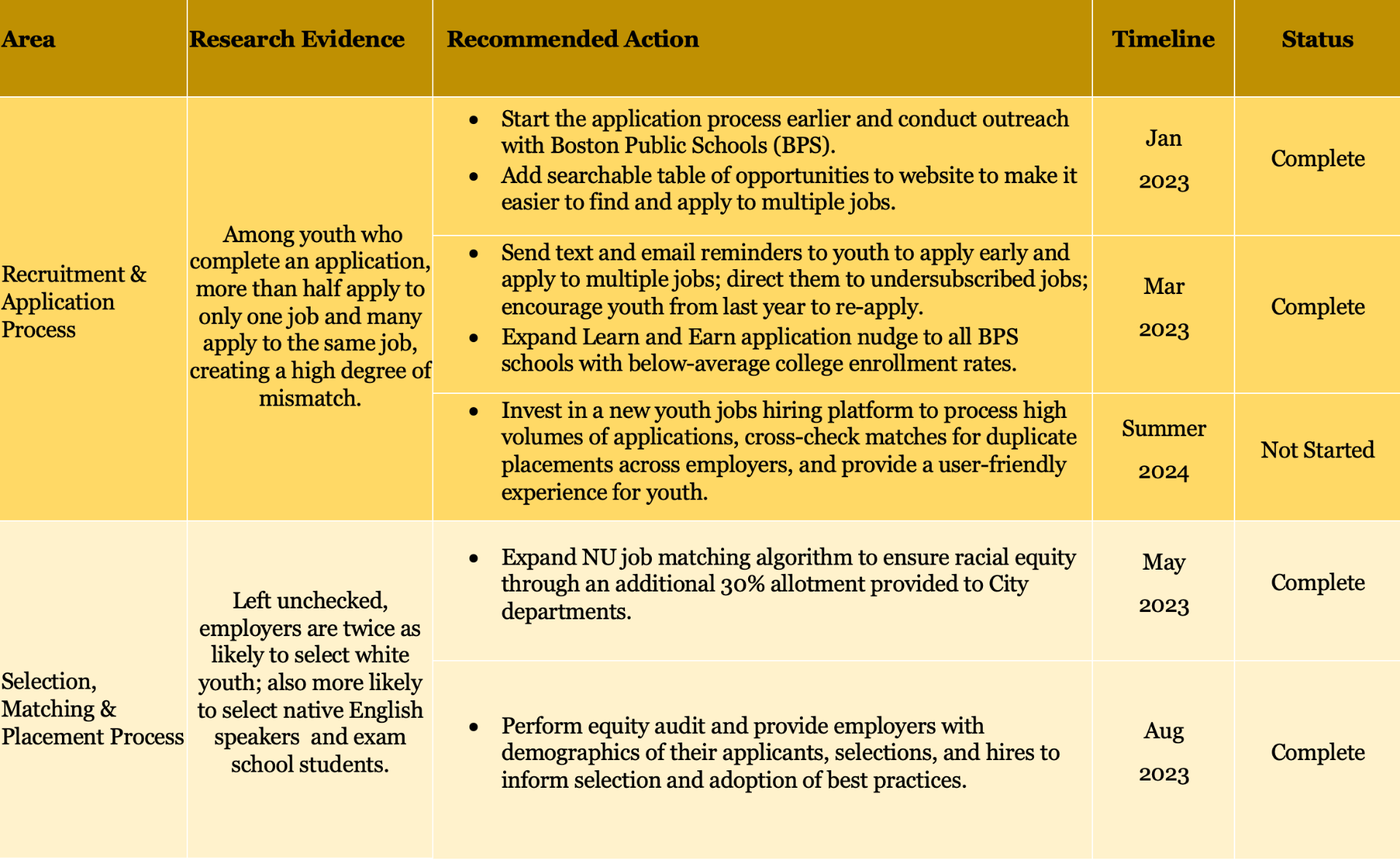

Enhance Application and Selection Processes

Our first set of recommendations focused on enhancing the City’s application and selection processes to increase access and fill as many positions as possible (see Table 2). In addition to recommending that OYEO start the application process earlier and increasing outreach through BPS, we also tested several behavioral nudges designed to increase access by broadening the pool of applicants. For example, we designed an information nudge to encourage students in targeted schools with below average college enrollment rates to apply to the Learn and Earn program, doubling the number of applications from such students. As a result, BPS expanded this nudge to students in similar schools as a way to expand access for youth who may be the first in their family to go to college. We also designed similar informational nudges to encourage youth to apply earlier and to more undersubscribed jobs to reduce the potential mismatch that can leave youth unemployed and jobs unfilled.

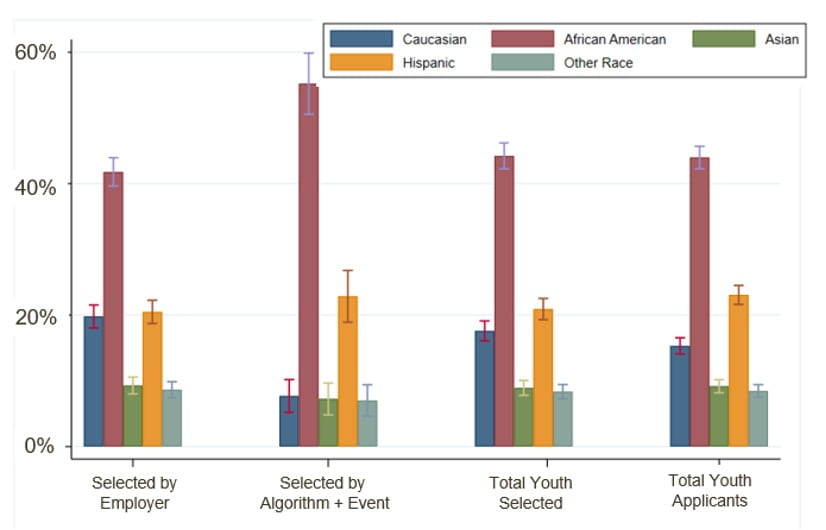

To further address issues related to equity in youth selections, we designed a job matching algorithm that was stratified by race and ethnicity. During the summer of 2022, we piloted this algorithm to back-fill open positions due to being either undersubscribed or if youth had failed to complete the hiring process. Our research shows that the algorithm was successful in improving equity across job placements by race and ethnicity. The combination of the job matching algorithm plus OYEO’s WeHire event ensured that the final list of youth the same racial and ethnic distribution as the total pool of SuccessLink applicants (see Figure 3). In 2023, the City expanded the use of the job matching algorithm through an additional 30 percent allotment provided to City departments. This was followed by an equity audit that provided City departments with the demographic breakdown of their applicants, selections, and hires to inform the adoption of best practices.

The one recommendation that has yet to be enacted is the investment in a new youth jobs hiring platform. Such a platform would require upwards of $1M to develop and implement yet it could be implemented across all of the intermediaries in the Boston summer jobs ecosystem. The goal would be to allow youth to seamlessly search for jobs on multiple criteria and easily apply to multiple positions; enable employers to cross-check placements prior to job making job offers and reduce duplication; and facilitate onboarding by making it easier to upload documents and complete the required steps in the hiring process.

Table 2. Recommendations to Enhance Application and Selection Processes

Figure 3. The NU job matching algorithm combined with the OYEO WeHire Event ensured that the total youth selected for a position had the same racial and ethnic distribution as the total pool of youth applicants

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data provided by the Office of Youth Employment and Opportunity

Improve Onboarding Process and Placement Quality

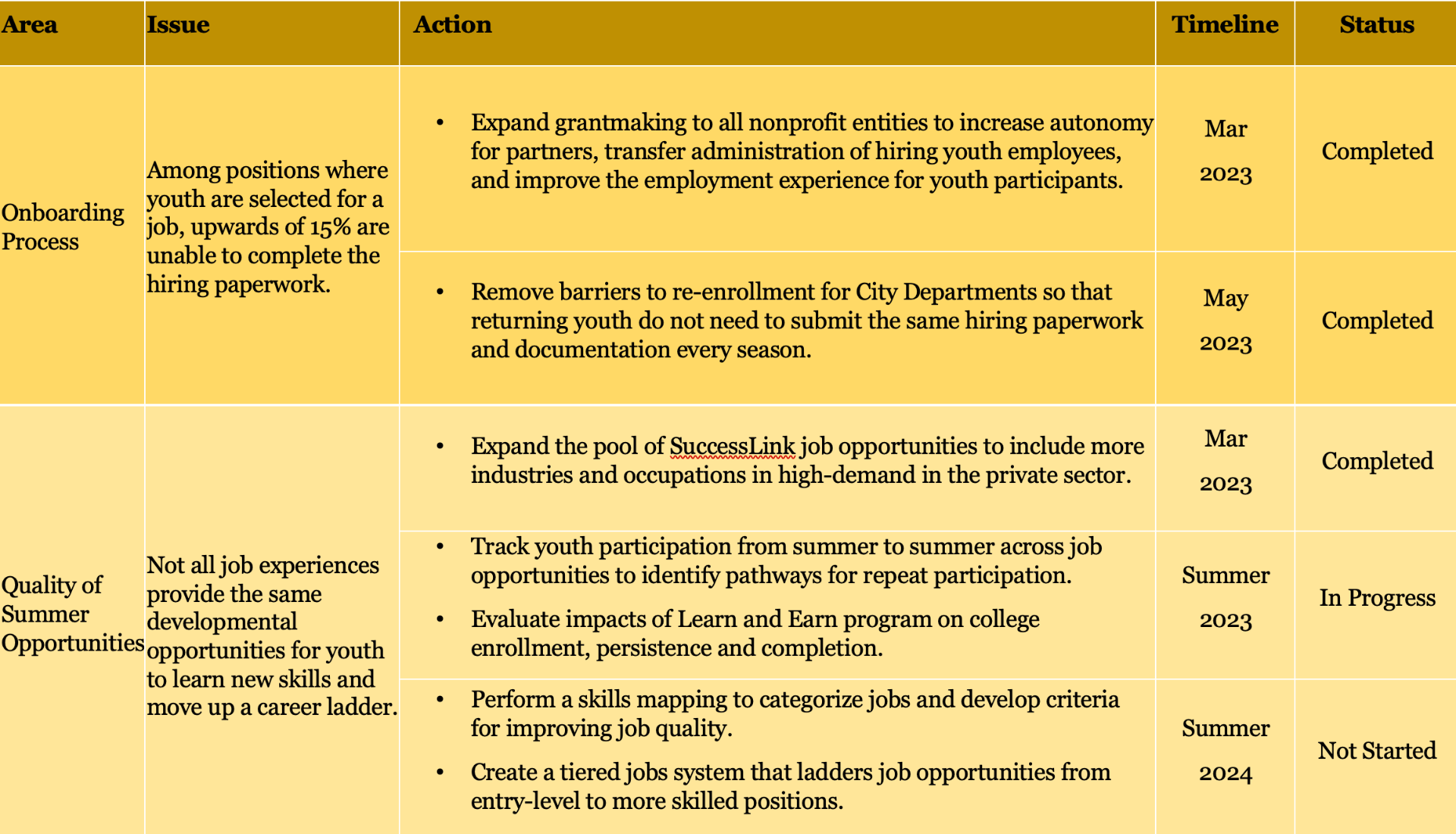

Our second set of recommendations aimed to increase the percentage of youth who complete the hiring process and improve the quality of summer opportunities. To improve onboarding, we recommended that OYEO expand grantmaking to all nonprofit entities so that only youth hired by City departments would be required to onboard through the iCIMS system. This increased autonomy for nonprofit partners to more seamlessly hire their youth employees and improve the employment experience for all participants. At the same time, the City removed barriers to re-enrollment for City Departments so that returning youth did not need to submit the same hiring paperwork if they had previously participated in the program. These changes drastically ensured that there were no unfilled SuccessLink positions in 2023 (see Figure 4).

To improve the quality of summer opportunities, we recommended that OYEO expand the pool of SuccessLink job opportunities, track youth participation over time, and create a tiered job system that ladders opportunities from summer to summer. During summer 2023, the City expanded their grant-making to include more industries and occupations in high-demand in the private sector such as healthcare, data science, and the green economy. In addition, the research team assembled a longitudinal dataset to identify pathways for repeat participation and to evaluate the outcome of the Learn and Earn program on college, enrollment, persistence, and completion. In 2024, Northeastern will perform a skills mapping to help OYEO categorize jobs into entry-level versus more skilled positions.

Table 3. Recommendations to Improve Onboarding Process and Quality of Summer Opportunities

Figure 4. By expanding grant-making to all non-profit partners and removing barriers to re-enrollment, no SuccessLink jobs were left unfilled in 2023

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data provided by OYEO

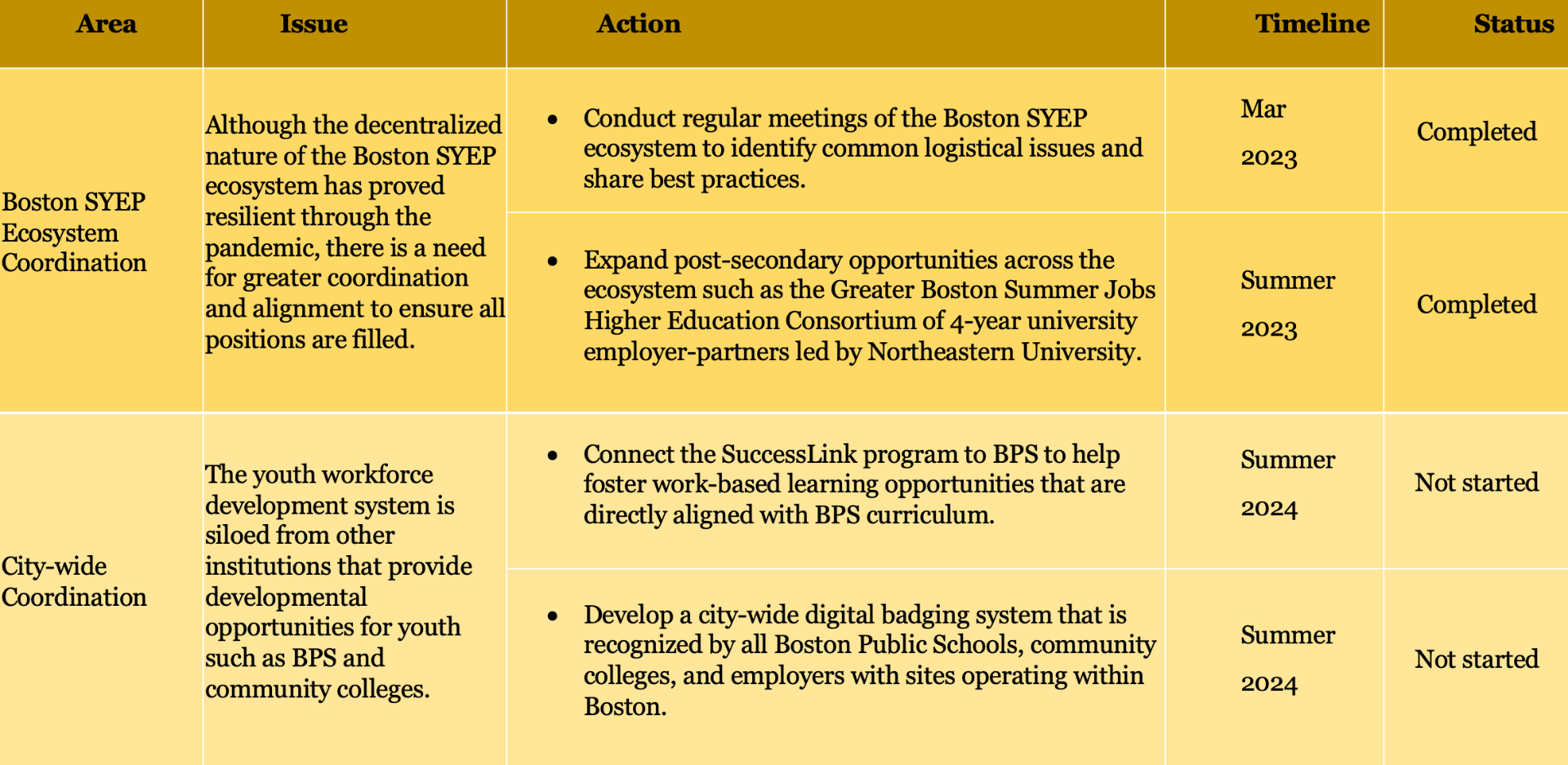

Increase Alignment and Coordination across the Ecosystem

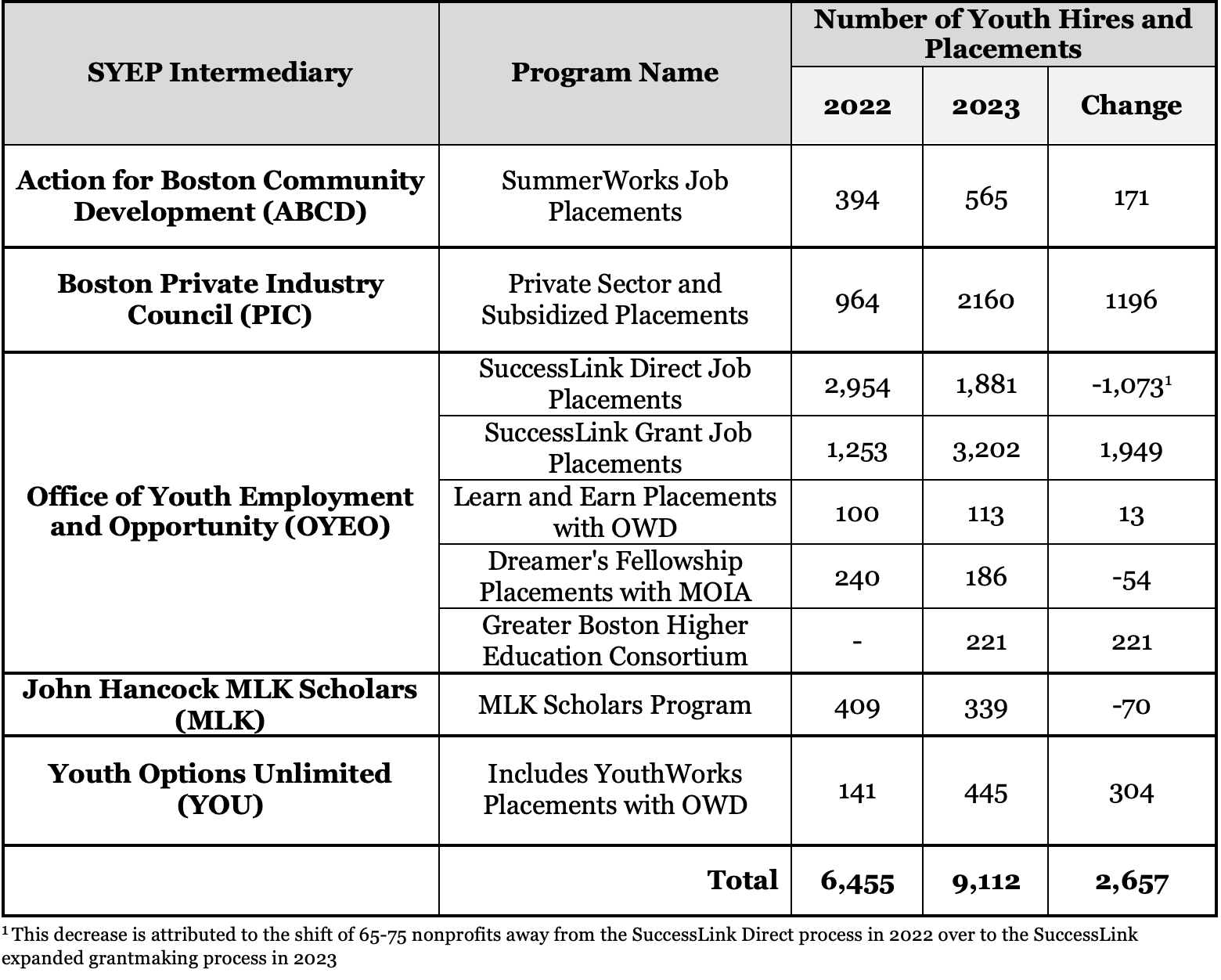

Our final set of recommendations was designed to increase alignment across the Boston SYEP intermediaries as well as foster coordination across City stakeholders. For example, OYEO held regular meetings that included both the intermediaries as well as some of the larger non-profit grantees to identify common logistical issues and share best practices. For the first time this also included the Greater Boston Summer Jobs Higher Education Consortium led by Northeastern University, expanding the Learn and Earn program to 4-year universities such as Tufts and the Boston Architectural College. This increased coordination and expansion resulted in over 9,000 youth employed across the Boston SYEP ecosystem in 2023, a foundational year to rebuild the program back to prior levels (See Table 4).

However, greater coordination and alignment is needed to ensure that youth are learning skills that will lead to a career pathway. We also recommended that in future years the City more directly connect the SuccessLink program to BPS to foster work-based learning opportunities that are aligned with BPS curriculum. Such a partnership could also lead to a City-wide digital badging system that is recognized not only by BPS but also community colleges and local companies to facilitate pathways into post-secondary training and employment.

Table 4. Recommendations to Improve Onboarding Process and Quality of Summer Opportunities

Table 5. By increasing coordination and expanding coalitions, the Boston SYEP employed over 9,000 youth across a wide range of skill-building opportunities.

Source: Author’s calculations based on data provided by the Office of Youth Employment and Opportunity.

Note: OYEO also oversees placement of youth through OWD (Office of Workforce Development) and MOIA (Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Advancement).

Conclusion

The innovation that came out of the Boston SYEP ecosystem during the pandemic highlighted the collective strength of the intermediaries as well as a need for more intentional strategic planning going forward. OYEO has demonstrated the ability to take a leadership role in providing data and analysis, strategic planning, and City resources that have increased both efficiency and equity. Continued investment is needed to ensure that the City of Boston is ready to improve the hiring process, increase job quality, and expand opportunities for young people by building a more holistic youth workforce development system for Boston’s youth.

Alicia Modestino is an Associate Professor of Economics and Public Policy and also the Research Director of the Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University. The Kitty and Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University is equally committed to producing state-of-the-art applied research and implementing effective policies and practices based on that research. Our goal is to integrate thought and action to achieve social justice through collaborative data-driven analysis and practice.

Rashad Cope is the Deputy Director of the Worker Empowerment Cabinet at the City of Boston. The Office of Youth Employment and Opportunity at the City of Boston exists to employ, develop and engage Boston’s youth. We do this by exposing youth to the workforce and connecting young people to opportunities for personal and professional growth. Our goal is to ensure youth are educated, equipped and empowered to transition successfully into adulthood. We do this through youth employment, youth career development training, and strategic partnerships and community engagement.

The authors thank Annie Duong of MLK Scholars, Mallory Jones of Youth Options Unlimited, Joe McLaughlin of the Boston Private Industry Council, and Jessica Rosario of Action for Boston Community Development for sharing their insights and data. We also thank the youth, parents, and employers who participated in our focus groups and interviews.

We are grateful for the generous financial support of the William T. Grant Foundation, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, the Spencer Foundation, and the American Institutes for Research

Community to Community (C2C) is an impact accelerator at Northeastern University designed to deepen the university’s commitment to community engaged research at each of its global campus locations. We strive to move the needle on societal problems at the local level, benefitting the areas our university calls home, while also promoting knowledge transfer across communities that are grounded in the local context.